The Japanese bubble economy of the 1980s 2 comments

(P.S: Sorry for any disturbances the advertisements above may have caused you)

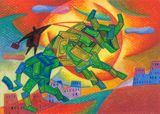

Speculative euphoria is often associated to cultural hubris. Again and again this has proven to be so, from the Tulipmania during the glory days of the Dutch, the market boom in New York at the start of the 20th century and recently again at the start of the 21st century. So it was with Japan in the 1980s.

Japan had become an export behemoth by the early 1980s, by virtue of her expertise and efficiency in mass production, innovation and branding. One can see in China today the Japan of the 1980s. Huge trade surpluses were run annually with the Western world who consumed Japanese exports. Further liquidity was available as Japanese companies started to borrow money on the Eurobond market for further expansion.

As with export economies that start to threaten Western jobs, Japan agreed at the 1985 Plaza Accord to revalue its yen currency. Clearly this would have an impact on its export competitiveness, and to alleviate fears, the Japanese government lowered interest rates to stimulate the domestic economy.

The massive amounts of easy liquidity that was made available to both companies and individuals due to the abovementioned factors led to an asset buying craze, both domestically and abroad. Genuine buyers, and then speculators as the asset boom ensued, bid up domestic property prices higher and higher, to the point where in 1990 the total Japanese property market was valued at four times that of the entire US. Japanese investors and companies, flush with the strong yen, embarked on further overseas asset buying binges such as landmark buildings, bonds and even paintings.

The stock market was the epitome of the liquidity-induced speculation fever. By the end of the 1980s, the market was valued at an astonishing 80 times PE; individual old-economy stocks such as textiles, services, marine, transportation etc were selling for more than 100 times PE. The public rushed in, but ultimately it turned out that insiders (brokers, rich investors, politicians, yakuza) would benefit most while the public usually were on the losing end of the daily stock churning. That one stock scandal involved a Prime Minister who ultimately had to resign (Recruit Cosmos scandal) indicated how high up the speculative fever and money-making craze had spread.

In 1990, the Bank of Japan started raising rates and the monetary tightening process accelerated over the year; the air slowly leaked out from the asset speculation bubble. However, it was not going to go away quietly. There were bank and broker collapses, as bad debts incurred by speculators no longer able to pay up rose to the fore; the biggest casualty was Yamaichi Securities, one of Japan's Big Four brokers. Japanese companies which had come to rely increasingly on profits from zaitech (financial engineering instruments) that rose together with the stock markets, now saw the other side of the coin, as these instruments incurred losses. And in the midst of it all, the loss of the wealth effect arising from speculative profits (stock market, property etc) meant that consumer demand was weakened, a condition exacerbated by the numerous capital investments made during the exuberant days that had created a lot of now redundant supply. The weak asset prices culminating in a deflationary spiral have lasted to this day, more than 10 years after the Japanese asset bubble was burst.

In retrospect, the transition of the Japanese economy from an export economy to a domestic consumption economy that was sparked by the Plaza Accord currency revaluation should have been closely monitored and actively managed by the Japanese financial authorities. Such a transition should ideally entail cheaper access to foreign goods (hence low consumer goods inflation) and prudent capital investments by export industries to increase productivity and efficiency. The fact that liquidity went instead into speculating in capital assets that multiplied in price was a dangerous signal of suboptimal resource allocation. Why the Japanese government did not take action earlier was inexplicable; or perhaps not, since as mentioned many government officials were also involved in making money for themsleves during the bubble.

The Japanese experience might also explain why China today hesitates in revaluing its renminbi currency until its capital markets are more mature.

References:

(1) Devil Take the Hindmost (by Edward Chancellor)

2 Comments:

Hello,

I liked your blog. I found many interesting information here.

I also give free info about denton forex trader training on my

href="http://www.WebTradingSystem.com">Forex Trading System site.

If you have time please visit my web site to get some free denton forex trader training

information.

Kind regards,

Nick

Interesting and informative post.

I was looking out for a company that could provide customized and affordable SEO services and with whom I could touchbase on a daily basis. I was very impressed with the professionalism and quick response time of Seo Traffic Spider and hired their full time SEO services. Its interesting that they not only offer a customized optimization plan but also provide a superb discount on their SEO combinations.

I think this would be a helpful start for anyone looking out for highly professional seo services and who prioritize quick customer response time and chat availability. You can surely get it all here.

Post a Comment

<< Home