The South Sea Bubble 0 comments

(P.S: Sorry for any disturbances the advertisements above may have caused you)

1720 will be remembered for two great speculative orgies that ultimately left many individuals and companies in financial tatters. One was in France, the Mississippi bubble; the other in England, the South Sea bubble.

The England government had incurred massive debts from wars in previous years, and in order to relieve itself of this burden, it transferred its debt to the South Sea Company which was allowed to sell company shares to members of the public holding the government debt. It was in effect a share-for-debt exchange. The government paid an annuity to the South Sea Company for taking over its debt.

This in itself was an innocuous scheme, and I could compare it to the Real Estate Investment Trusts of today where investors own shares in the property trust which in turn pays them an annual yield derived from property rental income. However, the structure of the South Sea Company's deal with the government was peculiar in that it was allowed to issue a fixed number of shares that could be exchanged for government bonds held by the public. Clearly, the higher the market price of these shares, the more the bonds that could be absorbed by this fixed number of shares. Hence lay the problem: the company had strong reasons to inflate its share price and its strong link with the government meant the latter was not likely to question it.

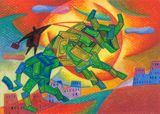

The share price was bid higher and higher by the public, aided by ample liquidity in the European financial system in 1720 and then by the sheer upward momentum of the price. "Bubble companies" brandishing dubious business plans also sprung up during this time. One cannot help but compare them with the Internet companies during the dot-com boom. Ironically, the whole South Sea induced bubble was ended by a Bubble Act which was actively promoted by the South Sea Company through Parliament, the company clearly believing that these bubble companies were sucking away liquidity that were the lifeblood of the company's share price momentum. Instead, the Act took away liquidity for all players, including the South Sea Company.

The company's share price rose from 130 pounds at the start of the mania to 1000 pounds at its peak and then back to 150 pounds, all within the space of one year. The whole populace was enveloped, from King George on down. One of the most famous victims was Sir Issac Newton, who famously said,"I can calculate the motions of the heavenly bodies, but not the madness of people." Indeed, this episode illustrates fully the ultimate futility of the "greater fool" theory, where people trade up a commodity higher and higher but then suddenly find that when the music stops, they are the ones without a chair.

References:

(1) The Four Pillars of Investing (by William Bernstein)

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home