The early-1990s Singapore residential property boom 23 comments

(P.S: Sorry for any disturbances the advertisements above may have caused you)

Nowadays, not a day passes without the papers reporting bullish news of prospective property deals; some argue that the residential property market is in the beginning of a new secular boom that could spread to the lower-end housing markets while others are significantly more cautious and cynical. In both camps the comparison is inevitably done with the property bull market of the early 1990s, when this asset class reached speculative heights and ultimately became a bubble that was pricked by consecutive blows of government regulatory measures and regional political trouble.

The fundamental case for property investing in the early 1990s was predicated on the rise of Singapore domestic demand. With economic stability and increased purchasing power built up over preceding years, it was time for asset enhancement in the 1990s. Young Singaporeans were being urged to marry and population control and immigration policies were being revised, adding to the demand for housing. Households were becoming increasingly double-income, increasing the purchasing power for big-ticket items. CPF balances were rising in-step with incomes, providing the financing means for purchasing expensive private property.

The sentimental case for property investing had been built up over the years. Since independence, the government had been promoting home ownership as a crucial tenet of nation building, and a huge majority of Singaporeans (~80-90%) owned the apartments they stayed in (mainly HDB). Hence increasingly over the years, property was seen as a good investment as prices were well-supported by the abovementioned government stand towards home ownership, the scarcity nature of Singapore property (the supply side), and perceived continued economic growth and stability (the demand side). Demand also trended towards more expensive private housing as people strove to upgrade their lifestyles. Many fellow Singaporeans will remember the Singapore dream built on the material five Cs: career/cash, credit cards, car, condominium, country club membership. Hence snob appeal and social aspirations accounted for an additional component of property demand meant for consumption.

Property as a comparative investing instrument was superior to other asset classes. There were few avenues for the less-educated to put their money: bonds had never been an Asian mass-market instrument, there was mass distrust of stocks due to their volatility (the market had shot up in 1993 and then dived back down in 1994), and money deposit rates were low. This also meant that housing loan rates were low (6% or less) and hence money was cheap. The unique standing of property as the only main investment instrument that could draw on the bulk of CPF funds enhanced its appeal; people tended not to think of it as "real money".

Given the above factors, property purchasing for consumption and investment soon turned into speculative buying. Stories of people buying an apartment for $500,000 and selling it for $700,000 a year later were part of the popular folklore. One apt description was that "people are buying property like groceries". This, of course, refers to the particular segment of property sales known as sub-sales, where people buy a property and then sell it off even before completion --- the most direct measure of speculative activity. At the height of the mania in the mid-1990s, there were the much-publicised midnight queues preceding condominium launches and the peaking of the highly reliable contrarian index known as the "market/coffeeshop auntie/uncle - buying, selling and recommending property" indicator.

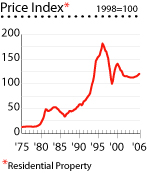

All segments of the residential market were booming, including newbuilds, resales, public (HDB) and private housing (condominiums). From 1986 to 1996, the private residential price index rose by about 440%. About two-thirds of this gain was in the early 1990s up to 1996. See below for a graphical representation. There was a big merry-go-round as sellers became buyers of other properties, whose sellers then sourced for new residences. Over 1992-2002, 58% of the 3-million population changed homes. Among private homeowners, it was almost 70%. This created an upward spiral of property prices that was exacerbated by the speculative elements.

In 1996 the government introduced regulations to cool property speculation, which included heavy taxes on profits made from property sold within three years of purchase --- a measure targeted at property speculators. It had to end somewhere. Rocketing property prices were increasing the costs of living, driving some citizens out of Singapore and decreasing its long-term business competitiveness. The private residential property market prices collapsed; the end of the bull market was confirmed by the 1997-98 Asian financial crisis that destroyed foreign demand drivers from the ASEAN region. With the exception of a minor mini-rally in 2000, private housing prices had dropped 30-40% by 2003, since they peaked in 2Q96. The HDB resales market was better although it was never to reach the heights of 1996, primarily because the government was careful about its impact on ordinary, less well-off Singaporeans.

Still, the damage had been done. The term "negative equity" is used to describe a situation where the difference of the investment's market value and the debt incurred in financing it is negative --- a predicament that many Singaporeans have been stuck in. The plunge in residential-property prices also had an impact on private consumption - fewer owners were able to withdraw equity from their homes to borrow against the increase in value to finance other consumption. As a result of heavy investments in property, Singaporeans are asset-rich and cash-poor, even counting their CPF retirement money. It is an example of how investments based on solid fundamentals can turn into speculative buying egged on by peer pressure to "make money while it lasts"; when the primary driver is sentiment and liquidity rather than fundamentals, it can be prone to sudden drying of liquidity that causes prices to plunge. In this case, the reversing of government policy towards controlling asset inflation just happened to be the catalyst that caused the U-turning of residential property prices. Even if it had not taken place, the hit would still have been suffered in the 1997 Asian financial crisis. It was a disaster to happen, and as always, it was one that was precipitated by human envy and greed, in my view.

References:

(1) Global Property Guide: Singapore

(2) The Star, May 2002: Curbing the property craze

(3) Asia Inc, Nov 1993: The Boredom Bubble

(4) Asiaweek, 1996: Testing Times

(5) FEER, Jul 2003: Singapore's housing glut